Hope Edelman: The Grief Journey Of Losing A Mother

Everyone’s grief is a very individual process. There is no one-size-fits-all. But when we lose someone who is dear to us, our life is changed forever. In this episode, join Karen Pulver in a conversation with three incredible women, Goddesses Lara, Vanessa, and Michelle, who have lost their mothers at various ages in their lives. She then sits down with Hope Edelman, the author of Motherless Daughters and The AfterGrief. Learn the beautiful memories they share, their grief journey, and how they have grown through the loss of their mothers to be mothers themselves. Hope then dives deep into the ways individuals cope and continue to have their arc of grief. As she states, “finding others that can understand our loss is the social support needed for bereavement.” Join us as we support each other through this journey of loss and learn how to come out on the other side with hope, courage, bravery, and love.

—

Watch the episode here:

Listen to the podcast here:

Hope Edelman: The Grief Journey Of Losing A Mother

Motherless Daughters, The After Grief, The Arc Of Loss

Thank you for joining us on the show. This episode is a compilation of a few different discussions. One is with Vanessa, who’s a Featured Goddess. She lost her mother years ago in the Lockerbie plane crash. The others were also with Vanessa, Featured Goddesses Lara and Michelle who also lost their mothers at a very young age. We had a beautiful conversation about the memory of their mothers, what their mothers taught them and what grief taught them moving forward in their lives. First, we will have a discussion with Vanessa, Michelle and Lara. We will be joined by guest Hope Edelman. She wrote one of her many books. This book that we will be discussing is The AfterGrief: Finding Your Way Along the Long Arc of Loss.

—

Thank you for joining us on the show. I am grateful. I have three amazing women that are here to talk with us about their mothers. I want to know about your moms. I’d like to know, Michelle. Can you tell me a bit about your mom? What were some qualities that you loved about her?

She grew up in a time where you had to behave and act a certain way. She did that for a while. She married and that wasn’t successful. She thought she had to do something. I watched her grow into her own person. It was so beautiful. I could think of it. She grew a backbone. My mom died at 37. When I say that, she was young. It was beautiful. She was a great mother in many ways. It was my first exposure to culture, whether it was museums, art galleries or plays. That was amazing. My first puff of a cigarette was from my mother. She’s funny and full of life. I knew she loved my sister and me fiercely.

Lara, can you tell us about your mom?

When we have a significant traumatic event, it divides our life story. Share on XI think of her as being this blanket of warmth. She was so giving. She was a wonderful mother, which she’s now my inspiration. At the time, thinking back to when she was raising my brothers and me, she drew from her background of being a social worker to help run our house. I have many different memories that are flooding in right now. One of them that I share with my kids all the time is that she would drop articles nearby if she thought one of us needed a little tip on something. She had books all around her all the time to try to work out all of the politics that were often happening surrounding our family. She was very supportive and always wanted the best for us.

As Michelle referred to, she had a love of theater. She was always planning wonderful outings for us and taking us on trips. I also have strong memories of her driving me to my figure skating lessons, my dance lessons and my acting lessons. She wanted me to find my thing. That was a wonderful thing that she brought to her parenting. She wanted everybody to find something that they had a passion for. That is something I cherish. I have brought that to my own kids. I want them to find something that they have a love and passion for. That is inspired by her.

Vanessa, can you tell us some qualities of your mom that you admire?

The fact that they are no longer here already puts them on a pedestal. We remember them in this magical, wonderful way as we should. Moms in general are pretty incredible. For my mom specifically, it’s a hybrid of Michelle and Lara’s comments. My mom was a very independent woman and had her own business at a time where women were not expected to work outside of the home. To see her as a foreigner, as a woman, create her business, be very determined and successful in it was a great role model for me. I didn’t realize at the time that she was a role model. I didn’t realize how much of a pioneer she was being at the time. In retrospect, I can look at her like that.

She was very loving. We had the house where when you left to go to school, the corner store or wherever, it always ended with I love you. Even if we were going to be back in 2.5 minutes, it was always I love you. The love was always there. She was also very strict, for which I am thankful. We have lots of love, laughter, travel and adventure. She’s an amazing woman. I would like to be like her in most ways. Not necessarily always but as a woman at my age, I can look at her as a mother, as a peer and say, “I understand why she did it that way but I’m going to do it this way.” I am forever grateful for all of the love and support. This is what my mother did. She gave me roots. Lara said this to you. Our job is to give kids roots and to give them wings. That’s what my mother did. She gave me the roots to know that I was on solid footing and that I was loved. She also gave me the wings to go explore and be brave.

Thank you for sharing and for being vulnerable to share this. I know it’s hard to think about it. I do want to go a little deeper. I spoke with Vanessa about when her mother passed away in a very tragic plane crash. I wanted to talk with Michelle and Lara about your mothers, with the grieving process that you had after they passed. I’m so curious to know about our guests who were going to be interviewing, Hope Edelman. She talks about grief and how certain ways that our society has told us that we’re supposed to grieve. We’re supposed to be over it. I don’t know if you’ve gotten this comment, “It happened so long ago. Why are you still thinking about it?” These are some of the things that Hope mentions in her book that people say in our society that time will heal. I don’t know if you’ve heard this. “In time, it will get easier.” What Hope says is it’s like an arc. It’s not like stages that you go through and then you’re done. I’m curious about the grieving. Michelle, would you like to tell us first about what happened and then how you grieved after?

That’s the part that makes me emotional. My mom was sick on and off from when she was 32 to 37 with breast cancer and had a misdiagnosis at some point. My sister and I were sheltered from it. We didn’t know a whole lot. To this day, there are things that I don’t know about her illness. I remember my family sheltered us thinking they were doing the best for us. She was at a hospital downtown in Toronto. We were up North. In the last two months, we got to see her once or twice. She eventually ended up in a coma. Nobody told us or let us see her. I’ll never forget when I did see her in her body movements. That was the last time I saw her.

In my case, we moved from the province of Ontario in Canada to Halifax, Nova Scotia. It’s a three-hour plane ride away to live with my mother’s brother and his family. It wasn’t at all a warm introduction. My sister and I were unwanted. I think about the way that they even told us. I was twelve at the time, almost thirteen and my sister was fifteen. I remember my aunt, my uncle’s wife, sitting me down and saying, “Your mother died,” period. There was no grieving. I didn’t know then. I didn’t have any knowledge of what it meant to lose somebody like that. I didn’t know that I needed to grieve. I knew I was sad. I had to go to a new school, new this and new that.

My grandmother was nursing my grandfather at the time, my mother’s parents. She was amazing but she was losing her husband, my grandfather, at the same time that we were sadly burying my mom. She had to be very stoic. He died three months later. She lost half her family. Nobody ever brought it up with us. It wasn’t a good situation. It took me many years to understand the grieving process. That’s where Hope comes in. Her book changed my life. It normalized so many of my behaviors that I didn’t even have a clue about. I thought I was so different. All of a sudden, there were reasons why I was behaving, thinking and feeling a certain way. That started my journey of learning and understanding myself and that whole process. That’s pretty much it.

I know that Hope also helped Lara. Can you share your story, Lara?

For me, I was 25 when my mom passed away but I say it was 24 because we were in the hospital. I was looking after her. I had decided to stop working because I wanted to be with her daily because she was unwell. I was 25 when she passed away but she wasn’t able to experience my 24th birthday. I became extremely strong. This breaking down didn’t happen so much. In the early days after she passed away, I did have my breaking down moments with my husband. I had just been married. I’m so blessed she got to be at my wedding. Something came over me. I did a lot of reading. I was also digging deep to learn about grieving.

It was a different world back in 1995. First of all, we weren’t looking at our phones on a daily basis. You couldn’t be looking up online to find out about support groups for loss, specifically mother loss. People didn’t talk openly about grieving. It was more of an attitude of you should get over it. I certainly didn’t get over it. I spent probably 80% of my time talking about how I was coping. Whenever I met a new friend, within the first five minutes of the conversation, they would know my mother had passed away. What happened to me was I found Hope’s book at a bookstore. It gave me a lot of strength. I felt like she spoke to me. It was someone saying, “I understand. Not only did you have a loss. You lost your mother who was your caregiver, your best friend, your cheer cheerleader. You’re going through a deep grieving process that is very different.”

After reading her book, I ended up having strength within me that evolved. In my mind, I felt like I was going to show the world how great my mother was. I was going to be strong. I was going to raise a strong family. I was going to have a good marriage. I was putting 100% in. Every day, I was thinking like, “Mom, you prepared me. I’m good.” I also wanted to have her friends and all the people who knew her to think she did it. She gave to her kids and her kids were ready. On top of it, she also began to give me some messages before she passed away when I would say things to her about when I have kids.

There was some discussion that once came up that she was looking to buy a place in Florida. I would say to her, “You’re going to go and spend so much time in Florida. Don’t you want to be around my kids?” I remember specifically, I was so young. She had leukemia. She wasn’t well a year or two before she told us that she had a blood disorder. She kept that quiet. It was during that period where she said to me, “I might be around but it’s your turn. It’s your family to raise.” She was dropping little messages to me about it’s time to fly. I am still grieving. It does not end. It’s a process. I talk about my mother and my family. I have three kids. They all know so much about her. I tell funny stories. She’s in the fabric of our lives.

That is exactly what Hope talks about in her book that she encourages. It’s to continue to have those conversations to keep our loved ones who have passed alive in our lives, whether it’d be with photos, stories or when you’re cooking, to tell your kids those kinds of things, “This is what my mom used to use in her cooking.” I’m curious. What are some ways that the three of you keep your mothers alive for your families? What are some things that you do that perhaps our audience can learn from? Michelle?

I talk about her a lot to my kids. They know some stories. I talk more about how I think she would love them and think they were so great. She was going through that change, becoming her own person and being so strong. My kids both are their own people. They have never been followers. They’ve always done their own thing, whether it works or it doesn’t. My mother would have respected that. I talked to them a lot about that and about things she introduced me to. I infused her. Lara, I loved it when you said, “In the fabric of your lives.” I thought that was beautifully said. I think they feel it. They know some sayings and things like that. Sadly, I was so young. She didn’t fully set the foundation. She did in terms of values and things like that but in terms of raising my kids, it was by trial, error and learning. I feel so grateful that I used the few tools that I did have.

Vanessa?

For me, I connect a lot with music that my mother loved listening to. There were a few songs that would always make my mother cry. There were a few songs that no matter where we work, she would dance. Those songs now for me invoke the exact same emotion. I will hear that song and I will weep. The other songs I will dance to. My kids are looking at me. They’re like, “Here she goes again. Is she going to cry or dance?” Sometimes when I’m crying, they’ll come and hug me because they know that it’s a memory of my mother. They feel the love that I feel I’ve lost even though I have the love, but the daily love that we would still be getting. They also see the joy of the songs that I will dance to. That it’s a great memory of my mom that I can be free, dance and enjoy that moment of remembering dancing with her.

We talk about my mom or I’ll tell them a story. We moved back from living abroad for a lot longer than we thought we were going to be. We had put all of the photo albums of the family in storage. I thought we were only going to be gone for a year. Years later, my kids have grown up without these photo albums. When we came back and unpacked everything, in that first week, I felt more at home, more grounded, more rooted as a family unit having the photo albums of my family, and of me growing up with my mother and everybody else. Being able to pass those images on to my children was amazing to be able to do that. That’s how I connect and keep her spirit.

What song did she like to dance to?

The loss of a mother to a daughter is essential to a female tragedy. Share on XIt’s Electric Avenue by Eddy Grant and Don’t You Want Me, Baby. There are plenty of them. The song that I’ll cry to is La Vie En Rose by Edith Piaf. What I’m frustrated by is that since you were younger, I never knew the story behind why it made her cry. I only knew that she cried but I didn’t know why.

Thank you for sharing that. Lara, how about you?

I’m going to carry on from what Vanessa said. My mother told me the first time she heard Neil Diamond’s Sweet Caroline, she was at Gray Rocks learning how to ski for the first time in her 30s with my dad. They danced to that. It was a new song. Every time Sweet Caroline comes on, I’m so joyful. It’s a lot of fun. My kids know that. I tell stories about her all the time. One thing that I find with my mom was a beautiful picture from when she was young in her 30s. As I walked down my stairs and I walked up to my stairs, I honestly have little conversations with her. I’ll look over at her photo and I’ll be like, “Things are good.” I’ll be having an internal discussion with her about, “I need your opinion.”

We have that picture on our stairway. We had someone come and do some work in our house. This person stopped, looked at this picture of my mom and said, “That looks like your youngest daughter.” That made me so happy. I use her cooking utensils. I use a ladle she used for cooking. It’s in my kitchen. She had a favorite quote that she had on our fridge. It’s an Aristotle quote saying, “It’s choice not chance that determines your destiny.” That’s always been my favorite quote. I put it up in my gym. She’s with me every day at my gym. Every opportunity I have to share a story about her, I do. Vanessa, sometimes we make choices that are a little bit different from what our mothers did for us. I think she’d be proud of me for making the different choices. We want to take the best of our childhood. Maybe make some changes along the way for our own family.

I’d like to ask one final question. If you can think of a way that you’ve changed in terms of a positive now that you’re older. Hope does talk about when we lose somebody close to us, there’s a positive part about how we change. I was trying to wrap my head around it and I was like, “What are you talking about?” As I was reading her book, The AfterGrief, she says, “We wouldn’t be the people we are if this didn’t happen.” What is 1 or 2 ways that you feel that you have grown from the experience? Vanessa?

Without question, it is the ability to take chances and be brave. It’s the notion that life is short and it can change at a moment’s notice. My mother died quite suddenly. For me, at a moment’s notice, my world was changed. With that, having it happen at a young age, realizing that life is short and it can change, I said, “That’s it. I’ve got to live this life as if it’s the only one I’ve got. I have to be brave. Go out there. Take chances. Go on adventures. Not get stuck in a rut or do anything that I am not 100% thrilled to be doing. Life is too short for that.” I went for it. I had no regrets and no turning back. My life since that moment has been forward. It’s an adventure. It’s everything. For that, I will always be grateful. It’s a positive that came from it.

Lara, how about you?

Without a doubt, I feel that with the deep grief came the very deep experience of life and living every moment to the fullest. I do see the benefit in experiencing or what you can take as a benefit to truly appreciate your life. I cherish the times with my loved ones. I don’t take it for granted. I try to experience life to the fullest as Vanessa said. Take chances and express myself to the people I love. I want them to know how I’m feeling. My relationships have been deeper because of my loss. I’ve also been influenced in trying to take care of myself to the best of my ability. I know we can’t control it all. Genes and circumstances are out of our control but I became very conscious of living a healthy life. I need to know that for my loved ones, I’m doing that. It’s a powerful experience to have deep grief and then be able to be in the moment of celebrating when you need to celebrate. I celebrate to the max. I will continue to do that.

Michelle?

I’m going to piggyback on what you said, Lara. My friendships mean the world to me. I know that that’s where I brought it from when my family life wasn’t so great. After my mother died, my friends were and are everything. I understand about keeping the good keeps close, knowing how important that is, fostering those relationships and my family as well. I’ve known from a young age that I was exposed to different things after my mother died that I wouldn’t have been. That’s hard because I give it all up to have my mother back in a heartbeat. Somebody has other plans for me. There’s that. Also, it made me stronger. For a long time, I was strong in different ways where I held everything. It took me a long time to realize that that was coping when I was young and I needed it. As an adult, I learned how to express and deal. There’s a lot of her in me. I’m unbelievably grateful for that. She was amazing.

Lara?

One more thing I was going to say is I did experience going through stages and I still do, that I don’t have patience for heavy, little issues as much. It was more so probably in the period after I lost my mother. For me, being in a traffic jam, being delayed at the airport or the little frustrations that sometimes set people off instantly changed. I began to realize what the real problem is. Having experienced a global pandemic in 2020, there’s a lot of people talking about resiliency. People who haven’t been touched by loss are beginning to understand what it means to be in situations that are out of their control. That’s the feeling. Hopefully, everybody will be a little more kind-hearted and chill. The people who haven’t had these ups and downs of loss, that’s where I would always find it frustrating to sit and listen to silliness.

Thank you all for sharing these wonderful stories about your mothers, how you have grieved, how you continue in the arc of grief, and how you keep your mothers in your hearts. I know that this will help a lot of readers. We’ll have our discussion with Hope next to see more about her book, The AfterGrief and Motherless Daughters. Thank you so much.

—

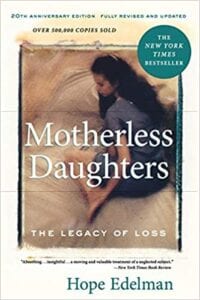

Hope Edelman has been writing, speaking and leading workshops and retreats in the bereavement field for more than 25 years. She was seventeen when she lost her mother to breast cancer and 40 when her father died. These are events that inspired her to offer grief education and support to those who cannot otherwise receive it. Her first book Motherless Daughters was number one New York Times bestseller and appeared on multiple bestseller lists worldwide. Her work has been translated into fourteen languages and published in eleven countries. Hope is the author of seven additional nonfiction books, including Motherless Mothers and the memoir, The Possibility of Everything. She was the recipient of the 2020 Community Educator Award from the Association for Death Education and Counseling and has won a Pushcart Prize for her creative nonfiction. In addition to writing and speaking, she’s a certified Martha Beck life coach and also leads nonfiction workshops to help writers tell, revisit and revise their stories of loss. Hope lives and works in Los Angeles and Iowa City.

—

Thank you for joining us on the show. We are all members of clubs. I am a member of the 50-plus club. I’m a member of the teacher’s club, the mom club, the cancer club. When you get to these clubs, meaning when something happens in your life and you signify, “I’m 50. I’m a member of the 50 club.” With the cancer, “I had cancer. I’m a member of the cancer club.” People around you, you can relate to them. You can talk to them. You can discuss how you’re feeling and how you’re anxious about certain things. Some of the clubs we like to be a part of. Some maybe we don’t. I know for me being part of the cancer club was something that I never ever expected or never wanted. Once I was in that club, I finally learned to deal with it. I talked to people. I realized that I’m in a cancer-free mode. That’s something to celebrate. When I was going through difficulties, I was able to talk to people who also went through those things. The grief club, that’s another club that many people are a member of or a part of whether they want to or not.

I had the opportunity to talk with Featured Goddesses, Vanessa, Lara and Michelle. They are in a club. We talked about their reactions after. I received texts from them that I’d like to share with you. Michelle said, “It’s a club that no one should ever be a member of, but I’m glad that we are members together. Thank you for helping me to process things that I haven’t thought of in a long time, a beautiful tribute to our mothers.” Vanessa replied, “Indeed a club. I’m always amazed how the thought of my mom can push around so many emotions that lower lips quiver and tears escape. Our conversation confirmed that I am not crazy. I will always miss my mom as you do as well.” Lara said, “I felt the same way. I felt very comfortable letting it all out with all of you. I’m looking forward with hope.” With that, I would like to welcome our guest author of many books including The AfterGrief: Finding Your Way Along the Long Arc of Loss. Hope Edelman, can you please join us on the show?

Story keepers help keep and share stories of loved ones alive. Share on XKaren, it’s so good to be here.

Thank you so much. We were very excited about you coming. It was a difficult day talking with the Featured Goddesses. It was a mixture of so many emotions. I’m grateful that you’re here and they can talk to you firsthand about some of the things that they experienced. One thing I wanted to ask you about the grief club, the rules of the grief club have changed and shifted. I remember reading the book with the stages of grief and remembering when people had passed away that we’re told in society to get over it, “Have you accepted it yet? It happened so long ago. Why are you still thinking about it?” What’s normal? I’m curious about your thoughts on that.

What’s normal for you isn’t what’s normal for me. One thing that we’ve learned is that grief is a very individual process. What you’re talking about is that the expectations of the grief club have shifted over time. The expectations and the culture of what we expect from grievers and what mourning should look like has also changed a great deal over time. You’re correct. There was quite a long period of time when the cultural message that grew out of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s work on the terminally ill, which was then applied to the mourners left behind. It led us to believe that we would go through stages and we would reach a state of acceptance. What happened was that the grievers around us who looked like they hadn’t adjusted the way that we thought they should were labeled unresolved. Their grief was relabeled pathological in the worst-case scenarios.

Everyone’s grief is so individual because of a number of factors. How old you were when someone died? Children and teenagers grieve differently than adults. How somebody died? If you’ve lost a loved one traumatically, that’s different than watching them deteriorate suddenly and traumatically. What kind of relationship did you have with that person? Even in families, we see siblings responding to the death of a parent differently because they had very different relationships with that parent. That temperament has a lot to do with it too, and prior experience with losses. That’s only about half the list. Grief is a very individual process. It’s hard to lay any expectations on any individual and say, “This is how it should be.” What I say is there is no one-size-fits-all. There isn’t even a one-size-fits-two.

What I love in your book is how you talk about grief as a constant motion. It’s reactivated by memories, sensory events or transitional events. When I’m talking with the women, some of them were saying, “I’ve been so strong all these years.” The talking was cathartic. It was difficult. There were tears but then they felt better that they could talk with each other, share, feel validated and feel safe. With that, I would like to invite them to join us. They have many questions to ask you. We’re going to start with Vanessa. Vanessa tragically lost her mom in the Lockerbie plane crash many years ago. She has some questions to ask you.

First of all, it’s an honor. Thank you so much for joining us. You have touched many women’s lives and us as well. You already touched on a point that I wanted to ask as we go through grief. I was fifteen when my mom passed away very publicly and shockingly. I’ve always questioned whether or not my character as an adult, how much of it was determined by my preexisting temperament? At fifteen, I’m not a fully developed adult and woman. There are many rules that I have yet to discover. In grief, you assume or you can get projected into a certain character. You can become a caregiver, a substance abuser or a lot of things. I found that I became a workhorse and overachiever, constantly working. How much of that was already determined prior to my mother’s death? How much was a result of my mother’s death? Is it even something that we can answer?

I’m going to answer it in two ways for you. I understand completely. I was seventeen when my mother died. I saw Anderson Cooper in a conversation with Stephen Colbert in August of 2020. It was quite something. He talked about how his father’s death when he was aged ten changed the trajectory of his life. I know that a lot of us feel that way. At Motherless Daughters retreats that I lead and in The AfterGrief, there’s a whole chapter about how when we have a significant traumatic event that occurs at any time in our lives, also when we’re young, it tends to divide our life story into periods of before and after. It cleaves. We were one person before or had one way of life before this event, and then this shocking, dramatic life–altering event happened. We had a whole segment that came after. Did you ever feel that there was life before and life after the accident, and they were two different segments?

Yes. There’s nothing that I do now that doesn’t somehow invoke a memory or an emotion. I feel that everything in my life after is somehow directly linked to that event.

That event set in motion another chain of events that determine the rest of your life. Many of them would have happened anyway. That’s a big mystery. We will never know. There’s an exercise I do with women, which is called The Before and After Exercise. I ask them to list all of the qualities and characteristics that they would use to describe themselves before their mother died. They make a whole long list. It’s often innocent, young, sweet, spoiled but sometimes it’s arrogant, hotheaded. We draw a line and on the other side of the page, we make a list of all the characteristics they would use to describe themselves after their moms died. It often became fit. It’s caretaker, hyper-independent, sad, more empathetic.

There’s a mix of what we might consider positive and negative qualities. They’re clear on how they felt their life wasn’t who they were in the before time and who they were in the after time. We turn the page and I say, “I’d like you to list all the characteristics that describe you when mother loss is removed from your story. Who did you come into this world to be? What traits or characteristics do you embody that are so baked into your DNA that they would be impervious to any event taking place?” Sometimes they can find them right away because it was on both sides of the other page in the before and the after. Sometimes they’ll say, “I was always creative. I always had a thirst for knowledge before and after.”

In my case, I was always highly sensitive long before my mom died. I was the child who would cry in restaurants if I saw an older person eating dinner alone because I assumed that they were lonely. I didn’t know that I’d eventually become middle age and be glad to eat alone because I could read my book and not be bothered. I was like that. Those are sometimes the characteristics that get amped up by a mother’s death or sometimes shut down but often amped up. What I mean to say is that when we think of our lives in terms of before and after, we’ve created a fractured narrative for ourselves. This exercise is an attempt to help you see that you have a continuous story.

That mother loss didn’t necessarily cleave your story in half or change it. It was one thing that happened to you among many things along the way. There is an overarching self that experienced it all. The women tend to find great relief knowing that. A fractured life story like, “I was one way before that. I can’t ever recapture and get back to,” is a sad and hard story to carry. When they think that there’s also this continuous self that experienced everything and that’s still who they are, it can bring them a sense of wholeness or inner peace.

I identify 100% with what you’re saying. I never did the exercise formally but I think that subconsciously, I have reflected on that very question since my mother passed away, more so maybe as an adult and as a mother. I do see the connection and the continuity of the life before and after using the person that I was before and the person that I am now. Thank you for validating, as you do so often, that the thought process I was on and the path I was following for me was the right one.

It’s an amazing, powerful exercise to do in a group as well. The group holds the space for everyone to have that experience together. That’s why we do it at the retreats. I do it in the online groups that I lead. My second question for you is more of a life coaching question because I’m also a certified life coach. Why is it important to you to know the answer to that question? What do you hope to get from the answer to that question?

I started asking myself that question in the last few years as my kids are growing up. They’re 12 and 14. In the years where I juggled a very intense career, children that needed me intensely, being pulled in multiple directions and not necessarily being able to do what I felt was a balancing act of all of them together. I questioned which part. It was non-negotiable that I would work less on my kids or my family. It left the question of can I work less on my career to establish a bigger balance? I was reluctant. I didn’t want to let go of my career because my career and my success was somehow linked to this workhorse ethic that I feel I derived from losing my mother. I didn’t want to let go of that either because it felt in a way that I was letting go of my mother and I didn’t want to do that. That’s where I started asking myself the question of, have I processed this enough? Have I found the balance that I want to have in my life without sacrificing something else?

Vanessa, you’re telling my story. I’m only a couple of years ahead of you. My kids are 19 and 23. You’ve articulated my story. Also, I asked that question because I was wondering if you had children and how old they were. It is also common, natural and almost expected that when your kids start approaching the age you were when your mom died, you’re able to see them in that before-period in your life. You may be thinking about what beautiful traits or characteristics they have that you shared, how can you help them hold on to them and not lose them at that same time, and have that trajectory that you had where you had to become a caretaker. That’s one of the reasons why women become so frightened that they also might die when their kids reach the same age they were. Thank you so much for sharing that because it’s common. I understand it from the depths of my soul. I’ve been there trying to balance kids and career. My career was very much part of the sense that I need to succeed quickly. I need to take care of myself. It was an adjustment to lost my mom at seventeen.

I also lost my father. There is an extra element of needing to take care of yourself, establish that very quickly and have that security that has been ripped from you at a young age. I was nineteen when my father passed away. There’s no question that that’s where the need for a career and the ability to always support myself, take care of myself and then eventually take care of my family has come in. My husband has lost both of his parents too. The magic number of how old your mother was when she died, will you make it past that age? Your children, ironically, I will be the same age that my mother was when she died when my son becomes the same age that I was. 2022 is going to be a load of fun.

In fact, this is such a big transition that we don’t have any cultural way to acknowledge that passage. At The AfterGrief initiative, I developed a ritual with a company that develops rituals. A template for people can create a ceremony around that event of reaching and passing the age. There’s a whole template of things that people can do. They can personalize it also. We have a way of acknowledging it either on our own, with our family or with a group of girlfriends saying, “I made it.” It’s an achievement for many of us. It’s bittersweet. It’s a way of saying, “I’ve separated my destiny from my parent.” I’m fourteen years past the age of my mom when she died. I can’t tell you how strange it is to be fourteen years older than my mother got to be. In a way, this feels like bonus years. I’ve heard that from a lot of women.

Vanessa, thank you. That was so powerful. Thank you for sharing that. Thank you, Hope. I’d like to move on to Lara. I know you have lots of questions.

Hope, I’m getting emotional just seeing your face. My journey started years ago when my mother passed away. I was 26 when she passed. There was no internet to search up for support. I was searching for support. While my mother was sick with cancer, I found a book that was supportive, Bernie Siegel’s philosophies of why bad things happen to good people. That book got me through a lot of hardship while she was sick. I then found your book. It was exactly what I needed. I have the whole Motherless Daughters book highlighted. I’ve passed it on to people who’ve lost their moms.

One of the things which touched me and I wrote down the quote that you started your chapter with. It’s that the loss of the mother to daughter is the essential female tragedy by Adrienne Rich. I needed to hear that validation. I knew that this loss in my life at the time was going to be hard. I knew it was going to be. I knew I was a strong person. I needed to hear all of these stories that you brought together. I remember reading that in your teen years it was the time to flourish and separate from your mother. In the adult years, it was time to reunite and form a new relationship as an adult. I knew I wasn’t going to have that. I can tell you, there was nothing available except for your book to get me through that. No one specialized in mother loss. The groups that were available to me were all types of loss group together. Your words in those stories that you shared got me through.

Even back when I was 26, I remember reading about the thought that there’s a fear that my life might end at the same time my mother’s did. Millions of things are coming through my head. Sometimes I’ll be talking and I’ll hear my mom’s voice. It’s coming out of my mouth. I’ll be like, “Hope said these things are going to happen.” When you turn around in the mirror, I don’t know how I remember this but I memorized where my mother had some freckles on her. I’m like, “I had that freckle that my mother had.” All of these things got me to be able to gain strength in my life. It was hard for me to come up with a question. I will ask you from your Motherless Mothers book. I have three kids. I was doing fine. I was strong but I labeled myself. As soon as I met a new friend in the first five minutes, they would know I had lost my mother. At that exercise, I stopped my life and started labeling it as I don’t have a mother. When I had my first child, I began to repair myself. I looked back into your book about Motherless Mothers. The information about the biological repair, can you explain a little bit more about having your own children can help the healing?

We get to recapture or recreate a facsimile of the relationship that we lost. I say facsimile because it can be done with a son as well as with a daughter. Although the mother-daughter relationship has that gendered connection. That’s the same as the one that we lost. We’re coming in from the other side. We can relate to, understand and feel closer to our mothers in a whole new way. We understand the mother’s love for the newborn and the child that they’re raising. That’s something we couldn’t simply have understood before. Sometimes while that can bring an enormous amount of satisfaction and a newfound love for the mother, it can also bring real sadness and grief. We now also recognize what the mother lost. The mom loved her children that much and had to leave them.

In The AfterGrief, that’s what I call a category of new old grief. New old grief is when you experience an old loss in a new way. You couldn’t have experienced the loss in this way until you got to a certain point in your life. Reaching and passing your parents’ age is another form of new old grief. I couldn’t have known what it was like to look at the world through the eyes of a 42-year-old until I turned 42, which was how old my mom was. I couldn’t even do it at 41. I got it at 42. I couldn’t know what my mother’s experience as a mother must have been like until I became a mother myself at 33. I couldn’t have pre-grieved that at seventeen when she died.

There are going to be those inflection points throughout your life, which is why I talk about the long arc of loss. We’re going to hit inflection points throughout our lives. We’re going to re-experience the loss in a different way. We’re going to have a new relationship with the set of facts that exists. My mom will always have died of breast cancer in 1980 when she was 42 and I was seventeen. That looked different when I was 33 and had my first child. It did look different again when I was 42. We can do a lot of reparative work. With Motherless Mothers, there’s often an impulse to go a little overboard too with the reparative work. All of the photos, all of the memories, just in case I’m not around to tell them later in life, I want to make sure they have everything they need. I don’t see that as a bad thing. Only if it starts getting in the way of other things that you might need to do or want to do.

I do want to share with you that I got an email, which is not a common email but it’s not one I haven’t gotten before. I’ve gotten a number of these. You mentioned reaching your twenties and feeling that need for connection with your mom. I don’t want them to go by because it’s important. That happens. If you’re younger than your mid-twenties when your mom dies, you will often reach your mid-twenties. You’ll watch your friends start having more woman to woman relationships with their moms and wish that you could do that too. Your mom’s not there and it’s another kind of new old grief.

I got a letter from a woman who said, “I am in end–stage ovarian cancer. I don’t know how much time I have left. Is there anything you can tell me I can do to help prepare my daughter for my loss?” These are heart-wrenching emails but they’re important. There are things that a mom can do when she’s conscious, aware and accepting that the inevitable will occur. I wrote to her in some general senses about, “Your daughter will miss you every day for the rest of her life. Make sure she has access to the memories. One way that you can do that is to create a team of story keepers. Assign them now. Ask your best friend from childhood if you’re still in touch with her if she will be your story keeper for your childhood stories. Ask your friend from high school, from college, from your first job, from new motherhood. Assign people. Make sure your daughter always knows how to find them. Probably in her mid-twenties, she’s going to want to know who you were as a woman and not just as a mom. They then can be available to her.”

That’s what we’re longing for. In our twenties, we start wanting to know who our mothers were as women. We don’t always have access to that information. We have to rely on other people’s stories. The more access we can have to those stories, the better. In my coaching practice, I often work with women who reached that point. We create a list of people they can go to and scripts that they can use to try to get some of the information that they want. I’m going to say 90% of the time people are more than willing to share stories with them. It’s almost as if they’d been waiting to talk about their friend or their sister too.

I have tried to gain that information from my mother’s friends through the years. One of the benefits of technology in the last years is that we’re able to reach out to people. One of my mother’s friends wrote a message to me and described some childhood experiences she had with my mother. It was all because of email. She expressed to me in that message that she felt bad that years ago she wasn’t able to share that. She didn’t keep in touch with me. I wrote back and said, “Don’t feel bad. Any information I can gain, I’m thrilled to have.” It was an incredible feeling. That is a brilliant idea. I love that.

It’s enormously healing to get back in touch with relatives and friends later too. As a seventeen-year-old, I spun around saying, “Where did everybody go? Why aren’t they here? Where are my mother’s friends? Where are the relatives?” It was years later when I reconnected with them. They were able to say sometimes, “I’m sorry, I wasn’t there for you. I was so devastated by your mother’s death. I could barely function.” As an adult, I could have compassion for them and understand that they needed to take care of themselves. They gave me the stories later. That was okay. We could reach a new more adult understanding of each other.

I know Michelle with her mother’s loss when she was twelve, I remember you saying that it was not talked about. You were placed with your aunt and uncle. Her parents were divorced. Tell us and if you have questions for Hope.

That revolves around my question. First, I want to say hi, Hope. I’m glad that Lara articulated it. Seeing you makes me so emotional. You changed my life through your book, which I read years ago. I’ll be forever grateful. You normalized things within me that I thought were so different and weird. I learned so much about who I was through reading your book. I was in the group that was the first Canadian chapter of Motherless Daughters in Canada. I’m in Toronto. I met you many years ago. As Karen touched upon, my question is it’s been 43 years since my mom died. I was twelve. She was 37. She was a baby.

Find others to connect with that can understand your loss. Share on XThis is another offshoot, another question. My mother was 37. I was 35 but I still think of her as older than me. She was my mom. It’s weird. I don’t know if you can relate or not. My question is I wasn’t allowed to grieve. I hadn’t had a death or something to grieve over. Over the years, I’ve done tons of therapy and tons of work. I’ve processed it. It’s been little bits and pieces. For many years after she died, I couldn’t grieve. There was no room and it wasn’t allowed. What advice would you give me or any other person that never got a chance to grieve in the moment and express?

I hear from a lot of people saying, “I never grieved my mother. I never got to grieve my father.” I think of it a little differently. Everyone grieves to the best of their ability at any given point in time. Sometimes that ability is very limited. With children, it’s often limited because the adults around them don’t allow it to happen, silence them or don’t support them. As a little twelve-year-old, you probably tried and wanted to be sad and grieve around your mom but were getting messages or pushback from the people around you that we need to move on or you’ll upset your dad, your aunt and uncle. When you say you didn’t get to grieve when you were twelve, what were the circumstances around that?

I moved to the province like a three-hour plane ride, to my uncle. I went with my sister. He didn’t want us at the time. They had their own family. They were more interested in us learning the rules of the house. They sat us down the morning that we arrived to give us the rules. They weren’t interested in that. My grandmother, God bless her, was nursing my grandfather, my mother’s father who died of cancer also three months later. She was so stoic. The message was, “This is your new life. Move on.”

It sounds like you’ve had to go into survival mode. Grief was the opposite of survival mode. Showing those emotions or grief sounds like it would threaten the status quo in this new family. That’s a story I hear a lot. We have to grieve in bits and pieces or later in adulthood. We go back and revisit and let go of the sorrow that we’ve been carrying all those years. Do it in a way that honors the twelve years that you spent with your mom and that loss. I wish we were still doing Motherless Daughters retreats in person. We had to go on hiatus because of COVID. We’re hoping to start them up again in the fall. This is exactly the kind of work that we do there where women are able to open boxes. Many of them have had to lock those boxes in order to cope and survive.

Their coping strategy has been to not open that box. What I hear very often in the circle is women say, “I’m afraid if I open it up and I start crying, I’ll never stop,” which is a metaphor. It’s physiologically impossible to start crying and never stop. What they mean is that there won’t be anyone there to support me, hold me or contain it. It will feel too big. We create a circle that contains it. We help everybody self-regulate. Nobody ever cries for more than 5 or 10 minutes max in a row. That’s completely acceptable and welcomed in our circle. It’s postponed grief or delayed grief. A lot of children were not allowed to grieve. I see it a lot when they’re with a dad especially if the dad remarries very quickly, the parents are divorced, a stepmother and children have to change home, moving to a new family or they’re with adults who cannot tolerate seeing a child’s pain. When the child stuffs it or suppresses it, the adults convince themselves that that kid is okay. They’re resilient. They’ve gotten over it. There’s no appreciation whatsoever for that child’s inner world. That is not as common now. What year did your mom die?

’77.

Mine was ’81. It was the dark ages of grief. In the ‘60s, the ‘70s, the ‘80s, it started shifting slowly in the ‘90s. By the 21st century, we had a better appreciation for the needs of children, families, bereavement centers and programs that began. Some of them are wonderful. All over the country and all over the world, I’m involved with several excellent ones. They’re still not everywhere. One good thing that COVID has done is made these services accessible to anyone anywhere because they used to all be in person. We’re still ways away from getting support to every child and family. I know this is going to sound extreme but I’ll say it anyway. I believe that prohibiting a child from grieving is a form of emotional violence or emotional abuse. It does not allow that child to live in their authentic emotional self. It suppresses.

There are other responses later down the road. It often creates a sense of trauma around the mother and the mother loss of herself. My family also wouldn’t talk about my mother’s death. Even though my mom didn’t die suddenly, I witnessed a very rapid deterioration in the end as her cancer progressed. It was traumatizing for me as a child to watch it happen. Nobody ever would talk with me about that trauma. I kept having trauma responses for years every time I even thought about my mother. We know now therapeutically that could have been addressed. It wouldn’t have taken a lot but it never was. It took more than a decade before I got there. That was a decade of trauma responses. Some women are talking about 30, 40 years of that until they are able to have a safe place where they can work through it with support.

My family sheltered us away from my mom. She was in the hospital for the last two months. They wouldn’t let us see her. They let us go in right before she died. She was in a coma. I won’t go into the movements in what it was like. When you were talking, I could see the image. It is horrible and traumatic. What was the term you used again when you said about trauma and abuse?

It’s probably the emotional violence for a child to not revisit that time period with them or allow them to express their feelings. My mother was in a coma for a few days at the end of her life. I do know what you’re talking about. The idea of that state going on for two months is unimaginable for me for a child to have to witness. For a long time after my mom died, I could only envision or remember her lying in the hospital bed. I could not get back to the images of the 42 years she had lived before those last three days. There are all kinds of modalities. There’s trauma-informed therapy, EMDR, EFT. There’s quite a lot that can help but we didn’t have any of that back then.

Nobody knew what to do with us. As Lara said, I’ve also helped people whether it’s a friend’s kids or whoever, where the kids are young and lost, not mostly a mother but a parent. I’m so glad that I can give advice to people and help them because we didn’t have that.

You do that on an informal basis or are you working?

I’m a social worker by training but it’s informal.

That is a way to give back once we understand the context of our own experience. Quite a lot of Motherless Daughters volunteer at bereavement centers. In fact, I’m doing a presentation for volunteers at a large bereavement center in the US. Where do motherless daughters and where do adults bereave as children, which is the wider category? Where do they tend to congregate? Where can we find them to help them along on their path? They often show up in the volunteer course at grief centers and bereavement organizations. They want to give the children what they didn’t get. They’re much more effective as volunteers if they’re getting the support that they need to. That’s something that I’m looking into. How can we help these volunteers become the best volunteers they can be by making sure they have the support they need when they’re reaching their life transitions and their anniversary events? Wanting to give to a child what you didn’t get is a very altruistic impulse but it’s not always the best reason to do that work if your real impulse is also to heal yourself.

Lara, you have a question.

I have been trying to help some young girls who’ve lost their mothers. I was very close to my dear friend who passed away from breast cancer. Her daughters were 17 and 19. Another friend of mine who’s 30 lost her mother. They all lost their mothers to cancer. Similar to my experience, it was post-traumatic stress from seeing the deterioration at the end, which is so difficult. I feel in Toronto, there’s a need for a Motherless Daughters Support Group. These women can’t find that.

There is one. Why don’t you email me? Right before COVID, I was coming to Toronto. We had it set up. We were doing a four-day Motherless Daughters Group. About an hour outside of Toronto, we had it all set up. We had to cancel it because of COVID. We will try to reactivate it. We still have the list. We were bringing the retreats internationally. We’re so excited. It was a whole scale-up process. It was growing. We’ve had to put it on hiatus but I will be in Toronto. There is a lot happening there. I’d love for you to be part of it and get the girls into this network. I don’t know how active it is during COVID but I imagine that most of these groups will start up again. If I come in to do any kind of workshop or retreat in Toronto, which I hope I will when we can travel, let’s make sure that they have access to it.

I have one question that is on the top of my mind that I wanted to ask you. Do you find that people who’ve experienced this mother loss have trouble? I have trouble with a balance with my kids. I want them to be independent. That is my goal. Even starting off when they were younger, maybe starting around the age of 10, 12, if we were talking about my mother, I would say things like, “I did not think I would be able to survive without my mom.” Quite often, I’d cry. I would say, “Trust me. You will be able to survive in your life if you have lost. You don’t think you will but you will. If there’s something that comes over you, you’ll be okay.” I would always feel the need to tell them that. I’ve always wanted them to be very independent. I let them do things a little bit before other of my friends allow like drive on the highway. I want them to fly but I’m also the worst at saying goodbye. I’m a mess every time I let them do that. Do you find that that’s a common theme?

You’re telling my story. There’s a very fine line between preparing our children to be able to manage better without us than we felt prepared to manage without our mothers, and preparing them and making them scared of something that’s likely not going to happen. We’re always walking that line. How can I make sure that they’re competent enough to survive on their own in the world without being afraid that they’re going to have to? I’ve thought about that a lot. I have two daughters who are very different. They require different parenting skills. Temperamentally, they’re very different. We were a big traveling family. I always wanted my daughters to know how to make their way through the world.

Whenever we travel whether it was domestic or international, I made sure that they knew how to go out, explore and find their way back, that they knew how to use the Metro systems, that they knew how to take a train across the border. They became competent travelers and world travelers. That completely backfired on me when my daughter graduated from high school. She was only seventeen. She’s young for her class. She decided she’s going to Europe for a month with her boyfriend upon college graduation. Is that okay? Her boyfriend was raised in a very similar way. He was eighteen. She said, “Mom, you know I can do this. You’ve raised me to be able to do this.” I thought she’s right. She’s ready to step into that phase where she wants to put this into action. “How do I say no? I’ve taught you how to go out in the world and manage on your own but I’m not going to allow you to.” I thought about that.

Ultimately, the compromise was, “You can go.” She’s seventeen and ten months when she went. They had to create an itinerary and let us know where they were going to be. Let us know if they changed it. They needed to text or FaceTime us every night, which kids can do when they travel. They were extremely responsible about that. They were fine. They had no incidents whatsoever. I remember thinking I didn’t bargain for that part of this. Think ahead a little bit when you’re making those plans. I hear about that all the time. The flip side is something to be aware of. I learned this when I was writing Motherless Mothers and I took it to heart. I spoke with some of the daughters of these mothers who said, “I felt that my mother pushed me into independence to an extent where she wasn’t emotionally available to me. She was protecting me from getting too close to her so that I wouldn’t hurt so much if I lost her. I felt like I didn’t have the kind of closeness with her that I wanted.”

I was always trying to be very conscious of when it’s appropriate to let my kids know what I was doing and why I was doing it without hammering home all the time because your grandmother died. Also, still maintaining emotional closeness with them. I think in some ways for some women, having that emotional closeness is scary for them. If they’re afraid they’re going to die, they don’t want to have to be devastated at the thought of leaving their kids. We want to think that our kids can manage without us. In our minds, that idea that we’re going to die as our moms did and often at the same age is a very strong identification. I did start letting go of it when I passed my mother’s age at the time of death. Have you all passed your mom’s age at the time of death? Michelle, you have. What was that like for you?

That year was crazy. All hell broke loose for me. I was aware of it. Crazy things happen. I’ve let go of that while I passed the age. When I turned 50, I remember thinking, “I’m 50.” That lasted for two seconds and then I went, “I’m going to live for my mother. She was 37. I’m going to live for her. I’m going to live it up and enjoy every moment. She couldn’t but I’m here to do it for her.” It changed everything.

Can I ask a quick question? Are all of you above 50?

Vanessa is the young in here. You all are beautiful, smart and articulate. It drives home for me. Women in their 50s, we are at the top of our game.

I’m at the best point ever.

I’m 56. It’s an extraordinary decade. I appreciate it, Karen, that you give a platform to women to tell their stories at this age too.

It’s my mission. I was feeling guilty. My mom is still here. I was like, “How can I interview you? I haven’t experienced this. I brought along these ladies to do this because I can’t relate.” What I can relate with of my club was the cancer club of loss. Loss to what my life was like before. There was a moment where I knew I wasn’t going to die but when you hear cancer, you’re thinking, “I’m going to die. What’s going to happen?” That was like having to tell my kids those stories. What am I going to do? That was my next question. I do want to allow if it’s okay for timing, Vanessa and Michelle, if they have any more questions before Favorite Things.

My question was there are so many losses in 2020. Losses of jobs, losses of the way life was, losses from COVID, which I know you call bereavement overload in your book. I’m curious about that. What’s interesting is when I say that I can’t relate because my mom is still around, what I can relate to is that loss of control, and that loss of being put in a situation where you have to control your reactions and how you respond. That’s similar to when you lose a parent. With everything that happened in 2020, can you comment on all of those other types of losses that people have?

We have lost a whole way of life, at least temporarily. We’re plunged into a period of uncertainty because we don’t know when it’s coming back or what’s coming back. We are in a constant state of having to adjust to an ever-changing new cycle. It’s uncomfortable to live in the present. I’m not sure it’s even possible because we are temporal beings. We are always remembering the past and imagining the future. To try to bring that in and live in the present, maybe monks can do it but it’s hard for me. There are a lot of losses that are taking place. There is the loss of life. There are nearly 400,000 loved ones who’ve died to COVID. There are 2.8 million Americans who die every year of other causes. There’s a lot of loss.

There’s the loss of how to mourn our dead. We can’t do that in ways that are familiar and comforting to us. There is the loss of income or job security. For many of us, there’s a change in our living situations and certainly the loss of our social networks or access to our social networks. I’m a big proponent of the social aspect of grief and find things social support. We need to be with others who understand that need for validation and normalization. That search drives us to find other people who understand. That’s how the Motherless Daughters movement came together. Women who didn’t have mothers recognized they had a very different experience than women who did have mothers. The women who did have mothers could be sympathetic but they couldn’t empathize with our challenges or our plights.

It’s very important depending on what you’ve lost to try to find others to connect with who can understand that. For me, in 2020, I’m going through the pandemic like everybody but I’m also going through a divorce, empty nesting, and the rearrangement of my live event company. I have to sell the family house. I feel like I’m in such a bereavement overload unless I speak with people who are also going through a divorce and empty-nesting at the same time. What I get back is this is a hard year for everyone. I feel like I’m waving my arms saying, “I need someone to validate that this is real. This is a lot that I’m trying to juggle and manage.” Everyone’s having a hard time. It’s not like I’m so needy and I need attention.

I was leading a separation and divorce support group with a friend of mine who’s a therapist. We had twenty women. It was a relief for them. They said, “I can’t tell you how good it is to talk with other women who are going through exactly what I’m going through and trying to do it during a pandemic when everything is amped up or amped down and we can’t do things normally.” We want to be normalized and validated instead of marginalized. That’s the opposite, feeling marginalized or dismissed like, “You’re lost.” There’s no competition in suffering. That’s what the brilliant Elisabeth Kubler-Ross told us. There’s no competition in suffering but we get into this competition like, “My losses are bigger than your losses or harder to bear.” I don’t want to do that. I want to be around people who say, “This is hard. I know that because I’m going through it too. Let’s go through this together because we need each other.”

That’s the social support aspect of bereavement, which we’ve lost in this culture with the exception of support groups that help for the first year or two. The social aspect of bereavement used to be huge. It was natural. Funerals were big. Mourning periods were extensive. Lots of people participated. The village came together to mourn the passing of one of their own. In the twentieth century, there were a couple of big shifts. Nuclear families were left to deal with their grief on their own. If you were lucky, you had an extended family or religious community that could support you for a while. For the most part, nuclear families were left alone. They didn’t know what they were doing. They tried to get back to the status quo. It messed us up for a good 100 years. I hope that we’ll start coming back around and reclaiming some of what we lost. It would do our culture a great good.

I’ve attended three funerals over COVID via Zoom, graveside funerals, memorials and then Shivas. There are parts of the Zoom connection that I liked. We were given fifteen minutes one-on-one with the family where you don’t necessarily get if you’re in person. We were able to talk about memories of the person. That is something to think about as well. Vanessa, I want to open up to you if you have any other questions.

I do have another question. It touches on what everyone has already shared but perhaps a little bit more specific with our shared experience of having both lost a mother and a father. With your career, you showed your family that talking about bereavement was okay. You gave it to them when they didn’t let you talk about it at a younger age. Kudos to you. I feel that having lost my mom was huge. Shortly thereafter, I lost my father. It put me into another club as well. Even though I was nineteen and very close to being an orphan, I wasn’t technically an orphan. Being part of that club with other friends that have lost both of their parents, regardless of the age that you lose both of your parents, there is always an element of feeling like an orphan. Even if you have a husband, kids, there is an underlying feeling that you’re alone in this world. I wanted to ask if you have experienced that as well. Did it open up a sector for you professionally where you would evaluate that level of grief or that different kind of grief? If you have, did you find that there is a whole other level of how to process that as an adult?

The Motherless Daughters community has been asking for different subsets. One of the ones they asked for was a very early loss when you can’t remember someone who died. That’s why there’s a live event on that. They’ve also asked for reaching and passing a mother’s age at the time of death. They’ve also asked for one special group just for only children when you don’t have siblings that you can depend on, and for double parent loss at an early age. Those are going to be the next live events. I may spin them off into actual six-week groups for women in those categories because the issues are different. There’s no safety net. There’s a significant number of women who lose a mother and then have problematic dads, dealing with aging fathers. This is something different.

I will hope that these women will have a place where they can talk about what it feels like to not have a safety net as an adult, to go looking for a family and a partner. Sometimes you’re marrying for the family and not the partner. That’s a real thing that women talk about. Also, they say the weirdness of suddenly getting this big inheritance at a young age sometimes and being able to buy a house at 23. It makes you out of sync with your peers. They feel like there’s no one to talk to about things like that and not having grandparents for your children. There are very specific issues. Keep looking at HopeEdelman.com. That’s a good six-week group. We can do that online. It doesn’t have to be in person. Finding others who can understand your experience, validate and normalize it so that you don’t feel marginalized in the larger culture is critically important for our emotional wellbeing.

Thank you. You hit the nail on the head. That was so perfect.

Michelle, do you have a final question?

It’s more of a comment. It’s funny because years ago when I first heard of you and I read your book, there was you and your sister, if I recall. You were close enough in age to my sister and me. It was your mother. I remember thinking there were so many similarities. I’m also part of the getting divorced club. I signed my papers. I can relate on that level. I feel like this is the best part of my life. It was a very long marriage. I’m doing great but I want to share something because it pertains to that. It pertains to any kind of loss. For so many years, I had a fear of abandonment, rightfully so my father left at an early age and my mother died. I was so afraid that other people were going to leave in my life. When I was newly separated, I remember thinking about that fear of abandonment. I’m so much older. I know who I am. I’ve got the wisdom. I stopped in my tracks. I said, “I don’t have to be afraid. I’ve got this. I’m not going to leave me.” It’s corny but it was a big epiphany for me. My fear of abandonment is gone as simple as that.

I remember sitting at a Motherless Daughters Support Group. We did one in Connecticut in 2020. A social worker in New York who’s a motherless daughter was co-facilitating with me. We were talking about fears of abandonment. She said, “This is the fear of a child. As an adult, you cannot be abandoned because you will always have yourself. You are the competent adult that can take care of you.” It was a profound statement. That’s what I hear you saying too.

That’s exactly what you hear me saying. It fills me up so much. I don’t even know how to express that. There’s no need to be afraid.

I wanted to end by reading a paragraph that I love that’s at the end of your book, The AfterGrief: Finding Your Way Along the Long Arc of Loss. You said, “I promise you this. The pain you feel today won’t go away entirely but it will turn into something else. It will over time become something more bearable. It can become your traveling companion, not your burden. Until that day happens, hold out both of your hands. Place your grief in one and the other, accept the capacity to feel gratitude and awe for what you have witnessed and become. Bring them together palm to palm in front of you.” Thank you so much. We are so grateful to you for coming on. There’s much more to talk about and learn. If our guests and our audience want to reach you, they can contact you on your website.

It’s HopeEdelman.com and MotherlessDaughters.com.

Thank you so much for joining us on the show.

Thank you so much for having me here. It’s been a joy.

—

Welcome to Favorite Things with author Hope Edelman. We are here to talk about things that bring us happiness, joy, perhaps bring back good memories. I’m going to start. I’ve been sitting on this for the entire episode. I apologize if there are people who are against this but it is a fur coat. It’s probably almost 100 years old. It’s from my grandmother who passed away. The reason why I brought it is that she used to come to visit me. I was 7 or 8. I remember she would lay it on the floor for me to go lie on it. I would run over and lie down on it. Not only that, I would reach into the pockets and she would always have a little candy bar, a piece of gum or this crazy Sesame candy, which I don’t know who likes that. She liked it and it was special to her. She passed away. My mom had this coat. My mom gave it to me because she remembered how much I loved that memory. I’ve been tempted to change it into a shorter coat or a stall but I love to take it, lie down on it and remember my grandmother. I wanted to share that. Michelle, what did you bring along?

Mine’s on my phone. It’s probably my favorite picture of my mother. She loved us dearly. She looked beautiful there. We liked the matching outfits. They’re interesting. I love that picture so much. I need to blow it up and put it in my new place.

Where’s the picture you showed last time?

This is also my mom. I had to stop looking over at it because that’s when I would tear up.

Vanessa, what did you bring?

I brought two pictures. It touches on what we’ve already talked about. One of them is the picture of me and my mom when I was a baby. I didn’t realize but inadvertently or subconsciously, I placed it on the mantle right next to the picture of me with my daughter. The subject that we discussed about when you become a mom, you understand with full force the love that your mom had for you. To have these two pictures together, I appreciate the love that my mom and I understand that so thoroughly because of the love that I have for my kids. They’re next to each other on the mantle. They will be returned to the mantle like that. I will always look at it and remember this.

Lara?

Mine is also a photo. I’m a little teary from everybody’s descriptions because these pictures are so powerful. This is a picture of my mom when she was in her early 30s. It’s at a spot that I walked by on my staircase. I walk by it every day. I have some little mini-conversations with her. I’ll be walking up. I’ll have a quick check-in and say, “Things are good.” If I’m having a little bit of a moment where things aren’t so good, I’m like, “I’m going to remain calm.” I have a little interaction with her. It’s there. My kids look at it. Photos to me are powerful. I have more photos of her in my kitchen. They’re all over the place. It’s my way of connecting and keeping connected.

In response to a fear of abandonment, while others may leave, know that ...'I’m not going to leave me.' (You will always have you.) Share on XWe’ll help you talk about that in The AfterGrief about remembering those who pass perhaps through photos or like me through objects, something that has passed on. I should also share that I’m wearing a ring from Lara’s mom. She was my mother-in-law. This was a necklace that she had. The necklace was broken so I took the charm off and made it into a ring that I wear. I reached into my jewelry box to put on jewelry and I grabbed it. I was like, “That’s the ring she gave me.” Hope, what did you bring?

I brought something from my father’s side of the family. I talk so much about my mother. I don’t always talk about my father’s family. I brought this picture that sits on the little altar in my bedroom. That’s my great grandmother, Bertha, who’s my spirit animal. That is my grandmother on the lap of her father. That’s my grandmother, Anna. I’m going to guess this was taken in the early 1900s, right around then. We’re a self-contained family. I think about them a lot. He’s my namesake. It’s my great-grandfather, Herman. I’m named after him, Hope. I thought I would share that with all of you. I look at that every day and I think of them a lot.

In the Jewish religion, I know with my mother-in-law, her name starts with S. A lot of our children, we named S names. It’s a nice reminder of her. They’re all beautiful, intelligent, smart girls. Wouldn’t you say, Lara?

Yes.

Thank you so much for joining us on Favorite Things.

Important links:

- Motherless Daughters

- Motherless Mothers

- The Possibility of Everything

- The AfterGrief: Finding Your Way Along the Long Arc of Loss

- HopeEdelman.com

- MotherlessDaughters.com

About Hope Edelman

Hope Edelman has been writing, speaking, and leading workshops and retreats in the bereavement field for more than 25 years. She was 17 when she lost her mother to breast cancer and 40 when her father died, events that inspired her to offer grief education and support to those who cannot otherwise receive it.

Hope Edelman has been writing, speaking, and leading workshops and retreats in the bereavement field for more than 25 years. She was 17 when she lost her mother to breast cancer and 40 when her father died, events that inspired her to offer grief education and support to those who cannot otherwise receive it.

Hope’s first book, Motherless Daughters, was a #1 New York Times bestseller and appeared on multiple bestseller lists worldwide. Hope’s most recent book, The AfterGrief, offers an innovative new language for discussing the long arc of loss. She has published six additional books, including Motherless Mothers and the memoir, The Possibility of Everything. Her work has been translated into 14 languages and published in 11 countries.

Hope has also published articles and essays in numerous publications and anthologies, including The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Real Simple, Parade, and CNN.com. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University and a master’s degree in nonfiction writing from the University of Iowa. She is a certified Martha Beck Life Coach and has also done certificate training in narrative therapy.